Svalbard is an archipelago surrounded by the Barents Sea, at a latitude of nearly 80 degrees north. That’s 1300 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle. It is governed by Norway and there is an international agreement that restricts military uses in Svalbard. But that doesn’t mean the nearly three thousand locals are not nervous about Russia’s proximity and recent behaviour. There was a very interesting episode about that nervousness recently made by our ABC’s Foreign Correspondent program at this link (it’s also on YouTube).

https://iview.abc.net.au/show/foreign-correspondent/series/2024/video/NC2410H014S00

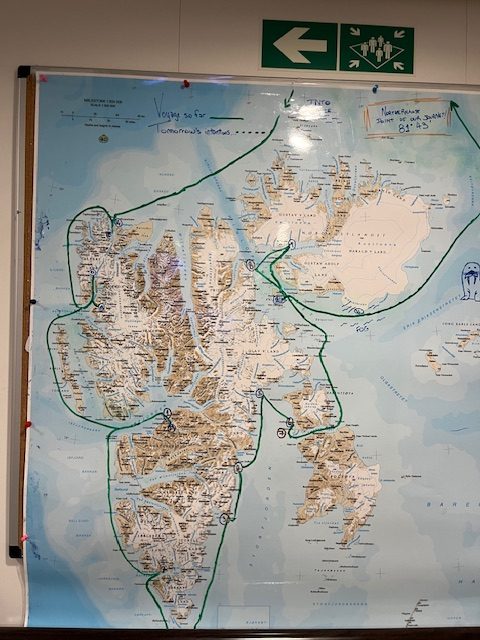

The green line on the map shows the voyage of the MV Greg Mortimer, under the Aurora Expeditions flag, the ship I sailed on in August 2024.

Svalbard’s capital is Longyearbyen and almost all of the permanent residents live there. On our town tour our guide tells us no one is allowed to die in Svalbard. This is because of the permafrost — it’s too tough to dig a grave. I resist the temptation to ask how they stop someone from dying, presumably she means you just can’t be buried there.

On many shops you will see this sign. It’s because if you leave the town limits, you must, by law, carry a gun. For the polar bears (which you’ll know from my first report on Svalbard). This one was on the supermarket door.

Svalbard isn’t only about polar bears and walruses (though I will post more about them soon). The main island, Spitsbergen, is home to the fascinating Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

Here is its Mission Statement: ‘From all across the globe, crates of seeds are sent here for safe and secure long-term storage in cold and dry rock vaults.’ Its website calls it a ‘Global Backstop’. Seed diversity, essential for our survival, is safeguarded by seed vaults in most countries (including Australia) and backup seeds are deposited in Svalbard by most countries around the world.

At the Svalbard Museum there’s a virtual tour of the GSV. It’s there I learned that there are some 5,000 species of seeds kept at -18 degrees Celsius. Actual seeds number over 1.3 million. The Vault opened in 2008 and by 2020 the first of its three chambers is full. The building tunnels some 130 metres into the mountain. It is predicted to be above global sea levels rising (fingers crossed).

You can’t go inside, only people depositing or withdrawing can do that. For deposits it opens three times a year. And if there is withdrawal, it’s is usually not a happy event because it means something has happened to make the seeds compromised or unavailable in their home country: an event like a flood, a fire, or a war.

Legal ownership remains vested in the country that deposited the seeds. One of the few withdrawals, so far, occurred when Syria’s own seed vault was threatened by conflicts and the government had to withdraw back up seeds from the Svalbard vault to replace what was lost. The seeds were then coaxed to life in more stable countries in order to replace their deposits in both Syria’s seed bank and Svalbard’s.

The brown building (above right) is where the overseeing of the vault is done. The goal is to keep safe seeds that represent each and every important crop on Earth and to ensure diversity. For example, there are more than 150,000 samples of rice and wheat.

You can look up the wesbite and read all the fascinating stats yourself here: Global Seed Vault

You can also read Svalbard Part One and Svalbard Part Two.